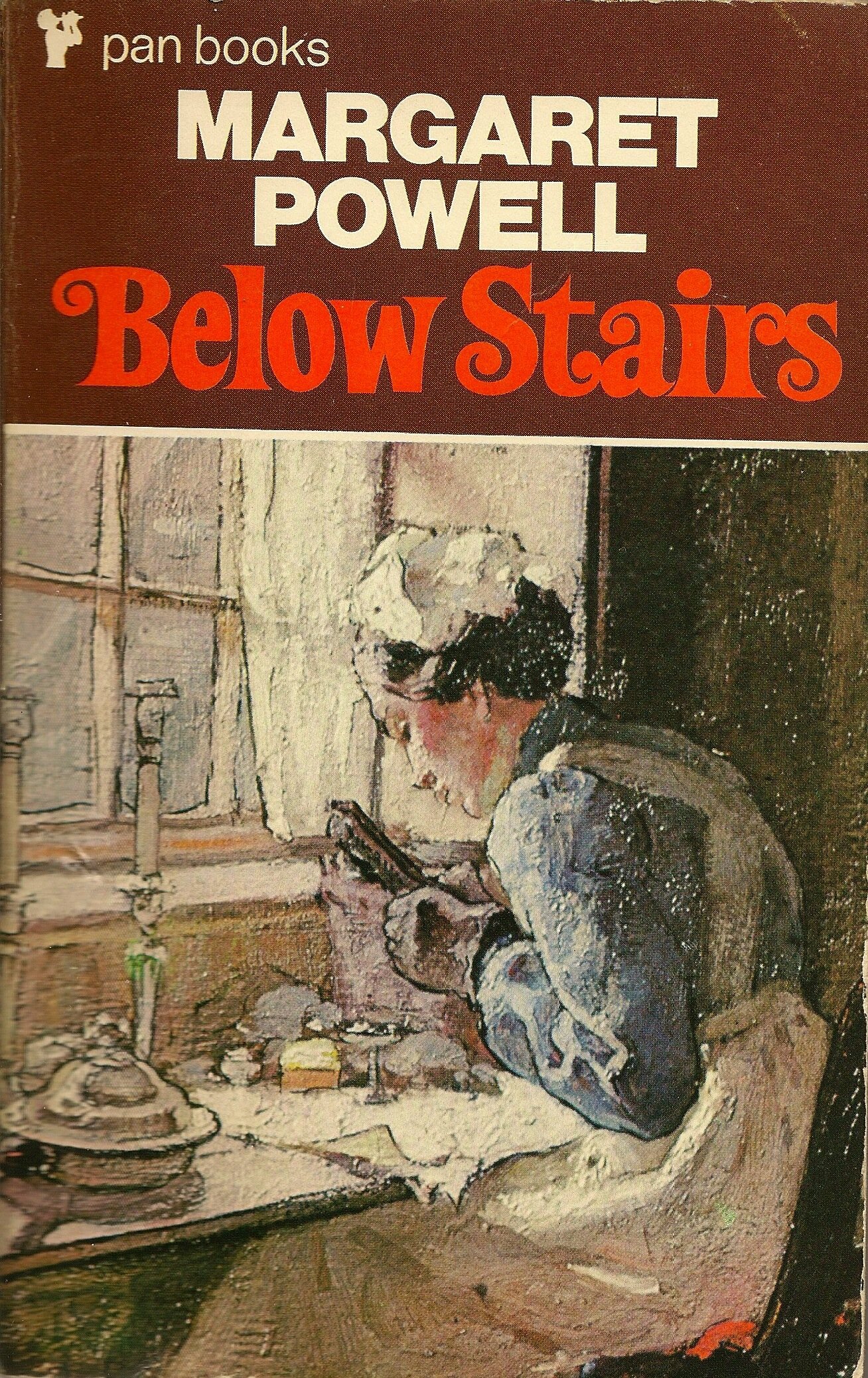

Review: Below Stairs by Margaret Powell

Isn’t it strange that the woman who inspired the tremendously popular servant-and-master TV series Upstairs Downstairs and Downton Abbey was a self-proclaimed feminist? Margaret Powell (1907-84), like thousands of working-class girls in 1920s England, had to go into service, because her family could not afford to support her, despite the fact that she had won a scholarship at school. Margaret started out as a kitchen maid, the lowest rank in the servant hierarchy, yet she managed in time to become a respected cook, and, as a mature woman, enrolled in further education classes, even attending lectures in philosophy. In later years, she regularly appeared in talk shows.

Powell was feisty, outspoken, and full of common sense, believing that "[t]hose people who say the rich should share what they’ve got are talking a lot of my eye and Betty Martin; it’s only because they haven’t got it they think that way. I wouldn’t reckon to share mine around." Aided by a ghostwriter, Powell’s memoir is peppered with delightful figures of speech which have since become rare, and which re-appear in the colourful idioms and proverbs used by Mrs. Bridges and Mrs. Patmore, the cooks in the aforementioned series. Picturesque eyewitness reports like Powell’s are rare, simply because most maids were not articulate enough to describe their working conditions. Powell talks about the hypocrisy of men setting up love nests, arguing, boldly for a 1960s book, that women whose husbands "don’t supply enough", should also be able to go somewhere where the men "are ready to oblige for a small fee", and complains that "we are the underprivileged sex, really and truly, in every way of life." She mentions the desperation of servant women who got pregnant out of wedlock, and then got dismissed on the spot, "your own home probably closed to you, nothing left but the streets or the workhouse."

"I suspected it was a nephew of Mrs Cutler’s. He was very young, probably in his early twenties, and a very handsome man. He had such an attractive voice that even to hear him say good morning used to make you feel frivolous. It sent shivers up and down you. I suspected him because on several occasions I discovered him on the back staircase, which was our staircase, a place where he certainly had no right to be at all. He used to say good morning or good afternoon to me in this marvellous, attractive voice of his. Some of the Americans have voices like that I have since discovered."

The staff then had to listen to long lectures on the "evils of such wanton behaviour" and "drivel" about the fact that "[n]o nice young man would ever suggest such a thing to a girl he hoped to marry," and that "no decent girl would ever let a man take advantage of her." Powell: "Whether they’re likely to marry you or not, they like to try their goods out first." Powell points out that servants didn’t have boyfriends, they had "followers", a disrespectful term which implied secret rendezvous, and informs us that maids were generally discouraged from seeing any men during their very limited time off. If a maid admitted she was a domestic, her date was likely to say "Oh, a skivvy!" and abandon her.

I’ll leave it to the reader to discover the many fascinating anecdotes and accounts of daily toil featured in Powell’s memoir, and briefly mention the television series created in the aftermath of Below Stairs, which spawned a number of strong female characters. In the 1970s production Upstairs Downstairs, spoilt upstairs brat Elizabeth Bellamy (Nicola Pagett) joins the suffragettes merely to cause a stir in her family and pesters her maid Rose (Jean Marsh) to join her, after which the two ends up being force-fed in a prison cell, completely ignoring the possibility that she could well be ruining Rose’s chances of remaining in work. Another interesting character is outspoken, daring servant Sarah (Pauline Collins), who resorts to tricks and white lies to survive in the cruel world she lives in. By the time Julian Fellowes had created Downton Abbey (2010-2015), the number of storylines about exemplary women had multiplied. Sybil, the earl’s youngest daughter, is a true feminist role model. She fights for the women’s vote, marries a chauffeur, volunteers as a nurse in the war, and helps Gwen (Rose Leslie), a maid, to get a more privileged job as a typist. Daisy (Sophie McShera), the petulant kitchen maid, wishes to better her education, and Sarah Bunting (Daisy Lewis), a young, leftwing schoolteacher, comes to her assistance. Even the ultra-conservative Countess of Grantham (Maggie Smith) is capable of showing latent feminist leanings when the situation calls for it.

Apart from Below Stairs, Frank Dawes’ reference book Not In Front Of The Servants (London, 1973) offers detailed information about domestic service in England between 1850 and 1939, after which time the servant class all but disappeared in the traditional sense. Following the overwhelming success of Downton Abbey, Margaret Powell’s classic was reprinted in 2011 as Below Stairs: The Bestselling Memoirs Of A 1920s Kitchen Maid, and continues to fascinate readers from all over the world.

In an effort to support Bookshop.org, this post contains affiliate links. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links. Thank you for the support!