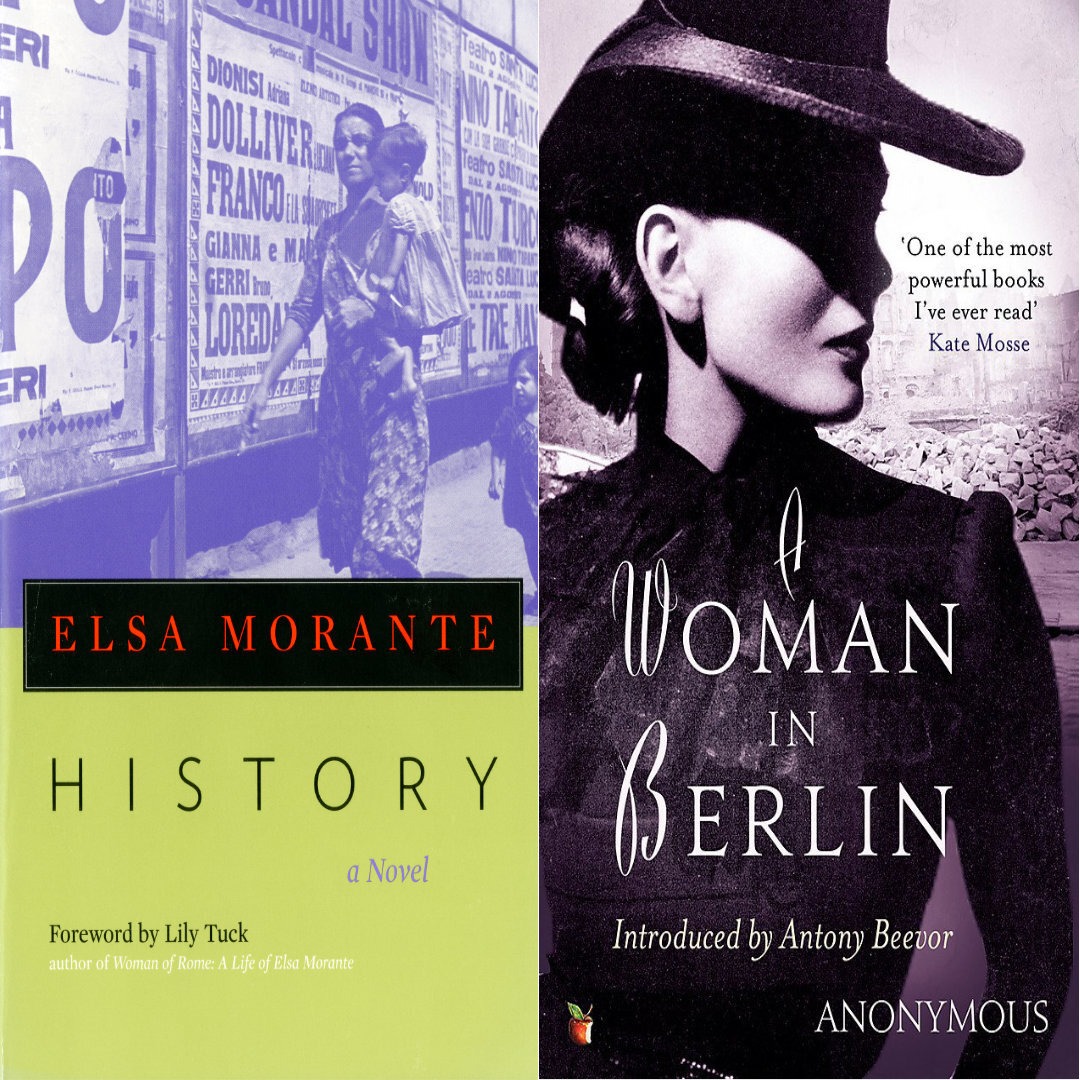

Review: History by Elsa Morante & A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in a Conquered City by Anonymous

Warning: This review discusses sexual assault.

During my time in quarantine, I have had the time to finally tackle my pile of books that I have meant to read because I wanted to or I feel obligated to because they are recommended to me. Presently I only have one novel left in that pile. The book that I looked forward to the most was History by Elsa Morante, and the novel that surprised me the most was A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in a Conquered City by Anonymous. After reading both of these novels back to back, I could not stop my brain from making connections between the two stories and their subject matter. Usually, we each review only one book, but this month I have decided to review both as the comparison between the two novels will lead to a stimulating conversation on women surviving during World War II.

History by Morante is a masterful blend of storytelling through the device of fictional micro-history and a non-fictional macro-history. Each part of the novel begins with an in-depth historical background into the precise year this chapter of the novel is occurring. It sets up the political and social climate in Italy at this time and also throughout the world. The micro-history, or fictional narrative, then follows this historical background that is narrated by someone who is close to the main character Ida but does not appear in the story. Ida Mancuso is a half-Jewish woman living in Rome at the start of World War II. Ida is a widow, a school teacher, and has one teenage son, Ninnuzzu. Ninnuzu is a political zealot and changes his loyalty from communism to archaism to whatever political group serves him best.

On the other hand, Ida is not politically active and lives a simple life that is structured by routine, that is until one fateful day. On this day, while coming home from shopping, a young Nazi soldier spots her, escorts her home, even carried her groceries up the stairs, and then rapes her. From this assault, Ida in her 50s becomes pregnant and gives birth to a blue-eyed baby boy named Guiseppe, but later nicknamed Useppe. With the delivery of Useppe, we are given another character in the novel whose insight into the war is that from a child's perspective, which I argue is one of the purest forms of perspectives there is.

From 1941 to 1947, we follow the lives of Ida, Useppe, and various other figures they encounter. Ida struggles to support both her and Useppe as Ninnuzzu goes off the fight, resources become scarce, they are bombed out of their home and lives with the constant fear of it becoming public that she is Jewish. At the same time, though, she lives with a deep shame of not being deported with the other Jews living in Rome and for having a son out of wedlock. However, Useppe gives her the strength to carry on as Ida does love him very much, and overall he is a very happy child who is blissfully in love with the world that he lives in. His adventures with his dog Bella around Rome and the people they encounter during them are a source of delight, especially when he starts writing poems. It is through Useppe that Ida can continue to live, and the reader wonders what would happen to her if he died.

The fictional story of Ida is that of an ordinary woman that I believe the author Elsa Morante knew or based her off of women she knew. This story is not that of a nurse, a spy, or even a woman who was politically active during World War II; it is the story of a woman who did her best to survive the war and protect her son. She is a compelling character in her own right because she tells a lesser-known tale. It is not until after the war that Ida and Usueppe begin to process the enormity of what they lived through, and it causes Useuppe to have seizures and Ida to age rapidly. It seems that the biggest challenge for both of them turned out to be how to live now that they no longer had to survive.

The next book, A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City, is another story about a woman surviving during World War II. The author is anonymous, but we do know that they are a female journalist and that they kept this diary during the time the Soviet Union's army began to take over Berlin. I want to take some time first to discuss the reception of the diary once it was published. The book was first published in English in the United States in 1954. It was not published in Germany until 1959, where the book was not successful at all because it discussed the taboo issue of rape. In 1985 the publisher Hans Magnus Enzensberger wanted to reprint the book, but the author would not allow it until she died. In 2001 Enzensberger was able to republish the book where it received critical acclaim and is a New York Times Book Review Editor's Choice. I find that the history of its publication is as important as the story itself as it adds to the idea of how shameful the subject of rape during the war was.

In her diary, Anonymous does not shy away from discussing the massive amount of rapes that occurred in Berlin under the Soviet take over, where it is thought that 100,000 women were assaulted. The author herself is repeatedly sexually assaulted until she finds a commanding officer who could 'protect' her from other men in exchange for sexual favors. She countlessly questions this arrangement and struggles with the notion if it is rape if she is giving herself 'freely,' and is she herself not a prostitute because she receives food and protection in exchange. The author's experiences were the same ones other women had as well, and you will encounter them in the journal passages as the author will ask them how often they were raped. I found this to be emotionally compelling as the author was trying to make the women feel like they were less alone in their experiences. It would not be until after Germany surrendered that arrangements like these would be seen as shameful by two groups of people, the men, and women who were not assaulted because they were able to be hidden away.

The diary also talks about what other means women had to do to survive. She worked as a laborer for a few weeks, fought to get her rations, stole glass to repair broken windows, and gave descriptions of her meals that could dwindle down to eating only nettles. What I found to be the most impressive thing about the author's writing is that she felt modern as if her writing style transcended the decades and will continue doing so. Her attitude of 'what does not kill you makes you stronger' gets her through her daily hardships as it is her mantra to remind herself to think of the good things that are happening in her life. Not only that but in her own right, she is a brilliant philosopher who elegantly finds the words to explain what it feels like to be German and how they all deserve what is happening to them, for they must atone for being the conqueror. I do not believe I have ever read any non-fictional war narrative that has ever shown this level of existentialism thinking as this author has provided or her overall sort of grace.

I am amazed that in one week, I managed to read both of these emotionally outstanding books about women in World War II. Both of these novels are powerful in different ways from Morantes blending of macro and microhistory to tell the fictional story of Ida and the truthful account of a woman who survived the conquering of Berlin by the Soviet Army. Through these two novels, we see the struggle that average women experienced, how this experience was different than that of the men who were on the front. Still, like the male narratives we have read about the war, we can see how, regardless of gender, both do their best to hold on to their humanity.

In an effort to support Bookshop.org, this post contains affiliate links. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links. Thank you for the support!